The Brookings Institution's P.W. Singer wrote an interesting piece for the Think Tank Town column in yesterday's Washington Post:

Winning the war on terrorism depends substantially on winning the war of ideas; unfortunately, by most metrics, the U.S. is getting its clock cleaned. Public polling shows massive anger directed at the U.S. and our credibility at an all time low. In a few short years, the U.S. has gone from being seen as the Cold War beacon of Coca Cola, McDonalds and freedom to the dark "Long War" home of Abu Ghraib, the Patriot Act and orange jumpsuits.

The deep and rapid deterioration of America's standing in the world is one of the greatest challenges the United States faces. More than just some lost popularity contest, the erosion of American credibility and leadership alienates our allies and reinforces the recruiting efforts of our foes. We are stocking the "sea" in which our enemies must "swim." It also effectively denies American ideas and policies a fair shake.

[snip]

Since 9-11, the Bush strategy has focused on a repetition of simple messages through controlled channels. But it has proven unrealistic for our complex information age, with our messages getting lost in the global cacophony of ideas. More importantly, the approach fails to account for the framework of interpretation. We focus on the messages we send; but the latest research shows we must equally focus on how people interpret and understand them.

Views have locked in and, unfortunately for America, people around the globe now look at any message from the U.S. government through a lens of doubt. This means even when we think we are saying the right thing, it can backfire; notice how such positive concepts as "democratization" are now largely reinterpreted in the Muslim world to mean "invasion." As the article sums it up, "Present strategic communication efforts by the U.S. and its allies rest on an outdated, 20th century message influence model of communication that is no longer effective in the complex global war of ideas."

Once people have seemingly made up their minds to interpret news and policies in a certain way, the study finds that only two things can change them. The first is receiving varied and complex sources of alternative information that force the individual to ask questions of what they earlier thought was true. As people get more and more information -- importantly from varied sources and leaders that they trust -- the old framework crumbles. A good illustration of this that the Bush administration can understand is how the once-strong levels of support for the Iraq war gradually tumbled over the last year. Early on, any bad news coming from Iraq was interpreted as being unpatriotic or something hyped by the left-wing "mainstream media." But, as the negative news became both continual and varied, with the sources ranging from journalists to retired generals, attitudes shifted even amongst the most fervent of the president's supporters. The lesson here is that U.S. strategic communications needs a similar shift from trying to spin simplistics to wrestling with complex realities. We must engage regional audiences in more than just pithy soundbites designed for Western audiences, but through a web of channels and local leaders that have far more validity than our own.

Singer goes on to suggest that the United States needs to 'reboot' its image by either solving the Arab-Israeli conflict or waiting until a new president enters office in January 2009.

The prospect of both options aren't great. Between the invasion of Iraq, its support for Israel's botched summer 2006 war against Hezbollah, and its general inattention to the issue, the Bush administration does not have the credibility to resolve the Arab-Israeli conflict. 'Rebooting' with new president isn't very unpalatable either because sitting on one's hands isn't appropriate behavior for a world-leading superpower -- especially when we are the ones who the world often looks to for immediate action.

All is not lost, however, because as Singer points out, image is driven by the expectations of others. Pulling of a miracle in the holy land and putting fresh blood are just two ways of shaking up public expectations with one drastic change. What about a trying a more gradual approach that involves moving on a group of smaller changes?

I'm a left-leaning libertarian, but I am not an ideologue. I don't think the Bush administration's foreign policy has any sinister intent nor do I think that Bush lied in the lead up to the Iraq War. I am very suspicious of the Bush administration's penchant for making simplistic, straw-man arguments. Their cognitive dissonance may look like obstinacy to some, but to those who do not implicitly trust the White House, it looks like they are trying to hide something.

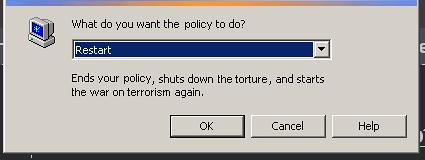

For me, reversing the administration's overly ambiguous policy on torture would go a long way towards an information war reboot. This needs to go much farther than "We don't torture" or "We no longer torture," it must also include:

1. An explicit acknowledgement that the practices now labelled torture were used on certain detainees.

2. A full accounting of the interrogation techniques that were used that are now prohibited.

3. An admission that even though the decision to use torture was made during an extraordinary time of crisis, it was wrong.

I'm willing to accept their rationale for initially resorting to torture in the first year or so of the war on terrorism. Policy-makers are limited by bounded rationality and the immediate post-9/11 period was defined by conditions that only exacerbate those bounds. They were under pressure to quickly devise policy responses to a threat they didn't understand using information that was unfamiliar and difficult to process.

Bad policy decisions were inevitable and some of them resulted in the torture of human beings. It was a mistake and we should apologize for our error in judgement and the undue harm that it caused. That simple message would go far in shaking up international perceptions of the United States.

Update: Retired Marine Generals Charles "Strategic Corporal" Krulak and Joseph Hoar completely agree.

Second Update: In the interest of presenting some balance, the Post's national security blogger William Arkin does not think repudiating torture will matter.

No comments:

Post a Comment